|

|

From the First Baalbak Festival to the Las Vegas Concert

Michel Mirhej Baklouk Loved Working with Fairuz

Turath Exclusive Interview Interview by Sami Asmar

Michel Baklouk played the riqq for Ziad Rahbani's recording Bilafrah in 1977 |

|

|

From the First Baalbak Festival to the Las Vegas Concert

Michel Mirhej Baklouk Loved Working with Fairuz

Turath Exclusive Interview Interview by Sami Asmar

Michel Baklouk played the riqq for Ziad Rahbani's recording Bilafrah in 1977 |

Asmar: Since you retired as the Rahbanis' lead percussionist and joined your family in New York, how often do you make contact with Fairuz.

Baklouk: Practically every time I travel to Lebanon. You see, I was not just another musician; I was practically a family member. The Rahbani Brothers trusted me with the musicians' salaries and coordinating the schedule of rehearsals. Before the age of computers, one of my tasks was to transcribe the notes for each instrument. After they compose a song they would notate the music but did not have time to make a sheet for the part of each instrument. Since I was versed in musical notation I took on that job. They would only notate one document, the conductor's book, which I was trusted with to make other copies. Some nights, after the stage debut of a new song, if they decided to make changes to it, the three of us would stay up late, one would compose, one would arrange the orchestration and I would copy to get it all done in time for a new rehearsal in the morning.

In a Baalbak Festival Dabke Dance (on tabla at far left) at age 29 Photo from Michel Baklouk (c) |

|

Asmar: How did you meet the Rahbanis?

Baklouk: I started at the music department of the Near East Radio Station in Jerusalem (Iza'at al-Sharq al-Adna). Due to the war of 1948, the station moved to Cyprus and later opened offices in Beirut. I moved with the station crew and ended up working in Beirut with many new musicians. The Rahbani Brothers also started their career with this radio station and I met them there. The station closed for good in 1956 as a result of the attack on the Suez Canal. Some time later, BBC Radio re-opened the facility abandoned by the Near East Radio and hired the same musicians. Then came the Baalbak Festival which was focused on bringing Western opera singers and large European orchestras. Assi and Mansur Rahbani felt that they could contribute with Lebanese folk music packaged beautifully for a festival. After the approval of the President of the Republic Kamil Sham'on, they were commissioned to proceed. They gathered up Wadi' al-Safi, Tawfiq al-Basha, Zaki Nasif, and many others, in addition to Fairuz, of course. Filimon Wahbe was often the comic relief although he composed great songs as well. Joseph Ayub, who played a folk flute, and I were often placed in costume on stage, not in the orchestra pit, to form a visual connection between the singers and the orchestra.

|

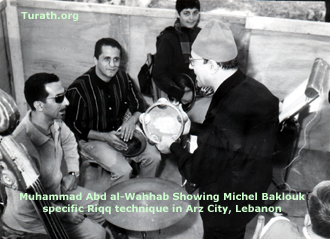

A Bright Day in Lebanon Egyptian composer Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab on a visit with the Rahbanis in Arz City, Lebanon. Michel Baklouk plays the riqq as Filimon Wahbe stands behind him and teenager Ziad Rahbani sits next to him. Joseph Ayub plays the minjayyra. Fairuz listens as husband Assi conducts. Mansur Rahbani is probably the person next to Assi. |

|

Asmar: Was Sabah involved in those projects then?

Baklouk: Sabah was not there at the beginning. If I remember correctly, one year Fairuz could not perform in the festival so Sabah performed instead and they named that show Mawwsim al-Izz (The Season of Greatness). Sabah was fantastic, probably at her peak, so was Wadi' al-Safi, some of his best work. Those were great days. Then the Damascus Expo started and our group would travel there to perform almost every year right after Baalbak. Some years we would repeat the Baalbak show in Damascus, some years Assi and Mansur prepared a new show for Damascus.

Asmar: Is that how you bonded with the Rahbanis?

Baklouk: They were like brothers to me, not friends. Assi, Mansur, Fairuz, and their general manager Sabri al-Sharif were very close to me. I spent a lot of time with them day and night in their homes in Antilas, Bikfayyah, and their office facility in Beirut.

Asmar: Did they show up to the office daily? How was their style of work?

Baklouk: They took their work extremely seriously. They spent endless hours in their office and they were inseparable. They had two adjacent offices. I would hear them come out and exchange feedback on their creative ideas in the common reception area, were they often received important visitors, and go back to their respective offices to fine-tune the work. After working all day, they'd go home but meet again at one of their homes and work some more.

Asmar: Did they specialize or divide the labor between them? Did Assi compose while Mansur wrote lyrics, for example, or vice versa?

Baklouk: They had their specialties but they both composed, they both wrote lyrics and they both arranged the orchestration. From what I saw they both did all the tasks required to produce the final material. If you had to look for a distinction, perhaps Assi had a strong passion for eastern music. Mansur was a specialist in large Western-style orchestration. For all practical purposes, the two brothers were musically interchangeable. They never wanted to take credit as individuals; they insisted on "Rahbani Brothers." In fact, if family members asked them who came up with that tune, each would say the other’s name at the same time, keeping all guessing. Having worked closely with them and having heard them discuss small details in front of me, I got to the point where I could guess sometimes who did what. I would guess for example that Mansur orchestrated Zahrat al-Mada'in; it is in his typical style. Listen to his work today, such as Al-Mutanbbi and you can detect similarities.

Asmar: How did Ziad start?

Baklouk: Ziad grew up in the world of music, had a lot of formal training and also absorbed the traditions of his father and uncle. He was around us as a child as I showed you in the pictures. What a way to start in the field!

Asmar: How do you feel about Fairuz now singing almost exclusively Ziad's compositions after the death of her husband? Is this a radical change? Too jazzy?

Baklouk: Ziad is entitled to experiment with jazz. He paid is dues in traditional Arab music and wrote great works in the eastern style. But you can tell he is still a Rahbani. Fairuz was never exclusive to the Rahbani Brothers compositions in the first place. She sang for Abd al-Wahhab (Sakan al-Layl) and two songs for Riyad al-Sunbati. She recently sang for the Syrian composer Muhammad Muhsin. Remember that some of her good songs were composed by Filimon Wahbe.

Asmar: Did Filimon compete with the Rahbanis?

Baklouk: No, he was part of the team. He would be in the meetings when they announce new lyrics they wrote. He would either take interest and ask to compose the melody or they would assign one to him. Fairuz really enjoyed working with Filimon, as did the entire orchestra because his tunes were full of tarab. He was a well known folk song writer before the Rahbanis but joining their team made him very famous.

Asmar: How did they ask you to come out of retirement and play in Las Vegas, and before that Dubai and Tunis?

Baklouk: Fairuz's staff sent me a fax inquiring about my availability and then directed me to meet them in Las Vegas, simple. I spent ten days there and lead the percussion section. We had several rehearsals with the orchestra and Fairuz. She ran the show herself, this time. In the old days, Assi and Mansur would prepare everything and she would come near the end for final rehearsals. But this was her show, her staff, and her choices of songs.

Asmar: In the old days, when the songs were new, how did she learn them? Was it fun to see her struggle at first, make mistakes, make mistakes, or ask questions??

Baklouk: They would give her the melody at home and then she would show up to the office, where they kept their instruments, for long practice sessions. The office was a better place to work and a professional setting. She was serious and a very hard working individual who did not take anything for granted. She did not make mistakes! She is a quick learner.

Asmar: What was your fondest memory of the Rahbanis?

Baklouk: Assi could not handle the news of any one member of the group being sick. He would lose sleep if anyone were ill. A musician got sick one day so Assi asked me to personally take him to his personal physician and spare no expense. I was very moved by that. Another time, we were in a recording studio for the musical Petra, and one musician (a wind instrument) got a heart attack. Although he turned out to be fine at the end, Assi almost freaked out and could not go back in the studio before getting good news for the doctors. It seemed like a weakness for him to see a colleague in pain.

Asmar: How was it like to work with other musicians?

Baklouk: I worked with everybody equally well. It seemed that my friend Joseph Ayyub, the flute player, and I became specialists in theatrical musicals. Whenever a new one comes along, they'd call us and charge us with assembling a group. I recorded for the Anwar ensemble, Tawfiq al-Pasha, Caracalla, especially compositions by Walid Ghilmiyeh and Marcel Khalife, Zaki Nasif, and so on.

Asmar: Who are the percussion leaders now in Lebanon?

Baklouk: My former students. The conservatory taught my method and those who completed it graduated and got jobs. I was the first riqq player in the Arab world who read and notated music. That made me attractive to the educated composers who knew that all they had to do was hand me the score. With other musicians, they worried about the time and effort in spoon-feeding them the music because they could not read the notes.

Asmar: Which Egyptian musicians did you work with?

Baklouk: I worked with Kamal al-Tawil and al-Mugi when they came to Beirut. I worked for eight years with Farid al-Atrash recording songs for his movies. Farid was special; he refused to work with anybody else and had me manage the orchestra in addition to playing; Abboud Abd al-Al often lead the orchestra. One time when I was sick, Farid cancelled the rehearsal altogether. It was simply because I knew what he wanted; I was close enough to him musically that I could express his ideas without causing him a lot of effort. Of course, I worked with Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab when he came to Lebanon. He composed and recorded a number of songs for Fairuz. He also composed a song for Abd al-Halim Hafiz, Dayy al-Qanadil, that the Ranbani's orchestrated, so I worked on that project as well.

|

Article from Al-Hayat newspaper translated from Arabic by Turath.Org

The 70-year journey from Jerusalem to Cyprus

to Beirut… and finally New York Percussionist Michel Baklouk Remembers Fairuz, the Rahbanis, and the Masters of Lebanese Music Mohammad Hijazi, London Michel Baklouk is one of the pioneers of the world of rhythms and percussions in all its various and changing forms. His specialty is the riqq (tamborine), the instrument he used to govern the beat of the songs of the great singer Fairuz throughout her long and unique career. The riqq was also the shadow and loyal guard. “I always had my riqq on me, never left it anywhere or let anybody borrow it.” This strong relationship

between Baklouk and his riqq continues despite the changing times and

work conditions. The Rahbani

Brothers trusted him “to the point that I kept their original musical scores

and distributed copies to the musicians.”

He remembers the period of work with Fairuz and the Rahbani Brothers

warmly but with a sense of loss of the golden age, the period he calls ”living

with the brothers. He exclaims that the brothers loved their work, often stayed

up nights for it, and consulted with those around them about it.

And about Fairuz he says: ”she is very kind and she sings from her

heart.” Michel Baklouk is an experienced artist who is modest by his nature. He weaved throughout five decades of professional life, loving relationships with all the artists he worked with. He contributed to most of the musical activities as well as to teaching at the national conservatory. He still keeps his documents and has numerous students who acknowledge and appreciate him, as do his own teachers and colleagues. This is natural for an artist who proved his loyalty to his art and his colleagues. But times have changed, as have values. Michel was surprised when the book Eastern Percussion Methods by Elie al-Faqih was published, reviewed by Walid Ghilmiyya, Director of the National Conservatory. The author, a former student of Baklouk, took the material taught by Baklouk and adopted it into a book but, unfortunately, without any credit or reference to his teacher. This is unlike Baklouk who always acknowledges his own teachers and colleagues. He taught at the conservatory for 26 years during a period where no other percussionist in the Arab world was capable of reading musical notation. Many excellent percussionists in the field today have graduated from his program and remember him kindly and lovingly. Michel Baklouk, also known to many as Michel Mirhej, is the Lebanese riqq player of Palestinian origin who accompanied Fairuz for half a century. He grew in the institution of Lebanese music and lives his memories when he still occasionally connects with Fairuz in different parts of the world, such as when she called on him to come out of retirement to accompany her at recent concert in Tunis and Las Vegas. Seventy-year old Baklouk still maintains a perfect beat despite his age and has been actively working in New York with Palestinian composer/performer Simon Shaheen since 1989. He maintains an active social life and cares for his family, including his grandchildren, like he did at his peak. He is concentrating on bringing the last daughter in Lebanon to join the family in New York. Amongst all this, Baklouk still remembers every small detail of his long journey, especially beautiful period of working with the Rahbani Brothers. When asked about life in New York, the capital of the world, he answers very briefly that it is different from Lebanon. He feels that the Arab musicians are few and most are not formally trained to read music, and that the only active and rising ensemble is that of Simon Shaheen. His unenthusiastic short answer is expected from a person who lived during the rise of the artistic movement in Lebanon and made a contribution to it, as modest as that may have been in the shadow of the giants who crystallized that experience with their own efforts. Those include Assi al-Rahbani, Tawfiq al-Basha, and Halim al-Rumi, his first boss at the radio station in Jerusalem, where worked prior to migrations that led him, against his wishes, eventually to the land of Uncle Sam. Michel Baklouk was born in Jerusalem in 1928. His father, died when he was only eleven, in the city of Safad in northern Palestine. That led to his transfer into a boarding Catholic school where he learned music. He reminisces those days: “we learned to use our fingers to represent the musical scale, five lines and four spaces.” He also learned singing at that school. “We chanted eight voices in religious and social occasions.” He graduated from school in 1945 and joined the Ministry of Works in Jerusalem and was assigned to the telephone services and then the YMCA across from the King David Hotel. He remembers the explosion at the hotel (by a Zionist terrorist group) and was injured because his work was very close. In 1947, he joined the Near East Radio, headed by Halim al-Rumi, as a telephone operator. Michel Baklouk remembers that beginning as follows: “Mr. Rumi, the radio station manager, had heard that I play the tabla (hand drum) and noticed that I always tapped on my desk rhythmically. So he offered me to join the station’s orchestra, which was comprised of Arab and foreign musicians. Joining that orchestra was a tragic circumstance since the Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948 forced his foreign colleagues to leave. He then requested formal transfer from the administrative department to the music department. But the war intensified and the entire station was forced to relocate to Cyprus. In 1949 Michel moved to Cyprus via Beirut and worked at the station until 1953. “Our broadcast was live on the air with all the singers. The management of the music department was rotated between Sabri al-Sharif, Halim al-Rumi, and Abd al-Rahman al-Khatib, the brother of singer Fadya Kamel.” In 1953, the orchestra moved to the station’s office in Beirut where Michel worked until 1956, the year the station was closed due to the Aggression of 1956 on Egypt. At about the same time, a recording studio company was started and headed by Sabri al-Sharif. Michel worked for that company until the British Broadcasting Corporation opened a facility for British war propaganda. Michel and many of his colleagues worked for the BBC until 1961 when they moved to the newly formed Lebanese radio station. In 1962, Michel started teaching percussion at the National Conservatory. During this difficult journey, Michel accompanied the pioneers of the modern Lebanese song, a genre that grew out of folk music yet exposed to world cultures. He worked with Halim al-Rumi, Tawfiq al-Basha, Zaki Nasif, the Rahbani Brothers, Filimon Wahbi, and others. He expanded his work as the music movement in Lebanon also expanded, starting in 1957, participating in the Baalbak Festivals. He then worked with visiting artists such as the giant stars Mohammad Abd al-Wahhab, Farid al-Atrash, and others. His primary work, however, was with the Rahbani Brothers and Fairuz, whom he first remembers as a choral singer in the radio station. “I was one of the musicians who were personally close to the brothers and Sabri al-Sharif since I could read music. I used to help them and still do. We had a warm and trusting relationship. They trusted me to bring them the needed musicians for projects without hesitation.” As for the relationship between the Rahbanis and their own colleagues, Michel remembers Filimon Wahbi who was a close friend of the Brothers and Fairuz. “Fairuz loved his compositions and was very conformable singing his songs.” Baklouk continues reminiscing, “The Rahbanis loved their work and stayed up nights for it. They also tended to consult others to seek the most honest musical feeling in their work.” He said of Farid al-Atrash “he was a true friend, he cared for me and I gave him all he needed. He was a hard working man and always showed up before the orchestra members reported to work.” Baklouk also worked with Abd al-Halim Hafez, Mohammad Abd al-Wahhab, Warda al-Jazairyya, Suad Mohammad, Wadi’ al-Safi, Sabah, Majida al-Rumi (the boss’s daughter) and others. He remembers Fairuz, however, in a special way. “She was kind and sang from the heart.” Michel also worked as a percussionist with the Palestinian couple Marwan Jarrar and his wife Badi’a who started a folk dance company for Lebanese dabka and supervised the folk arts part for the Baalbak Festival since its inception in 1957. He also worked with the most well known dancers of the time, including Tahiyya Karyoka, Samia Jamal, and Naima Akef. Michel Baklouk started as a young man in Jerusalem and got established in Lebanon. In the United States, he still offers his expertise and often receives honors by institutions in Washington, Texas, El Paso, and many others. |